Disguising Injustice: Unpacking Elon Musk’s NFL deal and centuries of systemic racism

NNPA Newswire

In a recent CNN Business exposé, journalist Oliver Darcy delves into the intricate dynamics surrounding the National Football League’s deliberations on renewing its $100 million deal with Elon Musk’s embattled social media platform, X, formerly Twitter. As Darcy unravels Musk’s unpredictable behavior and the alarming surge in hate on his platform, questions loom over the NFL’s potential renewal, fueling a broader debate on corporate responsibility in the face of societal issues.

In Darcy’s article, Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a renowned professor and senior associate dean for leadership studies at the Yale School of Management, focused on Musk’s anti-Semitism. Sonnenfeld paints Musk as a paradoxical figure, both a hero and a villain, whose turbulent conduct threatens the esteemed NFL brand. Emphatically, Sonnenfeld asserts, “Great brands such as the NFL cannot burn in the fires of his tantrums.”

All this leads the NFL into a precarious balancing act—attempting to appease its conservative base while avoiding toxic associations that could alienate its broader and more diverse fanbase.

However, the article becomes a powerful conduit for a broader societal query: Why doesn’t anti-blackness receive the same unequivocal condemnation? The tragic deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Philando Castile, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner—names indelibly etched in the history of the Black Lives Matter movement—symbolize recent hate crimes against African Americans and serve as the backdrop for this inquiry. Despite the Southern Poverty Law Center underlining these cases as emblematic of deadly police violence and systemic racism, the public response remains disparate, raising concerns about selective outrage.

The #BlackLivesMatter movement, which originated after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in 2012 and gained visibility following the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, stands as a contemporary fight against vigilantism and a legal system facilitating such injustices. Ida B. Wells launched a historical campaign against oppression during the Jim Crow era, and Patrisse Marie Cullors’ 2013 Facebook declaration reignited it.

Wells, a journalist and activist, confronted vigilante violence during her campaign against lynching in the late 19th century. Forced to relocate for her safety, Wells persisted in her crusade, publishing “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” This tract laid bare the dark and bloody record of the South, where 728 African Americans were lynched in the past eight years.

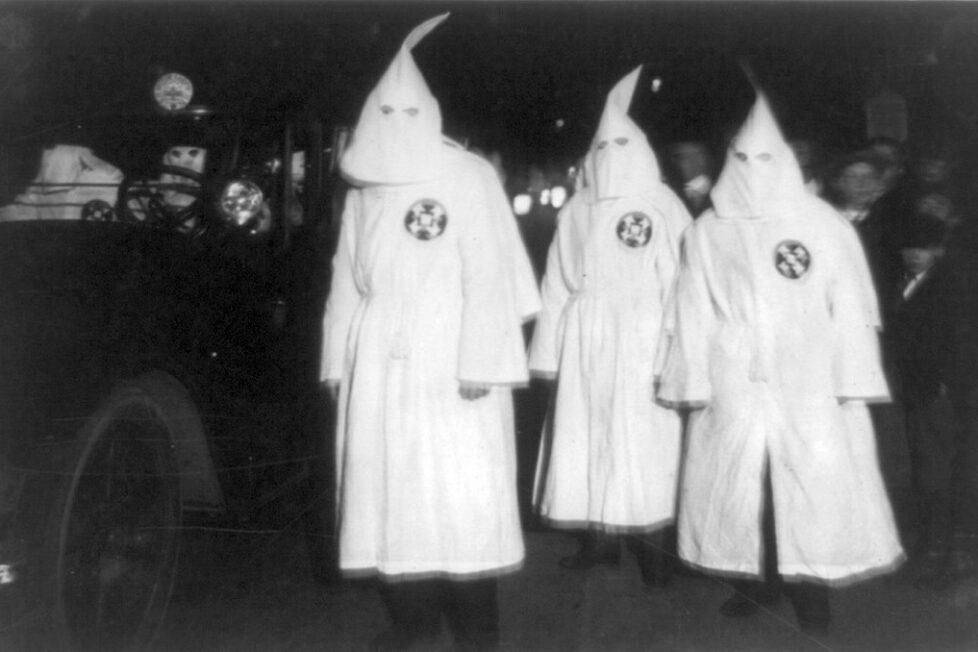

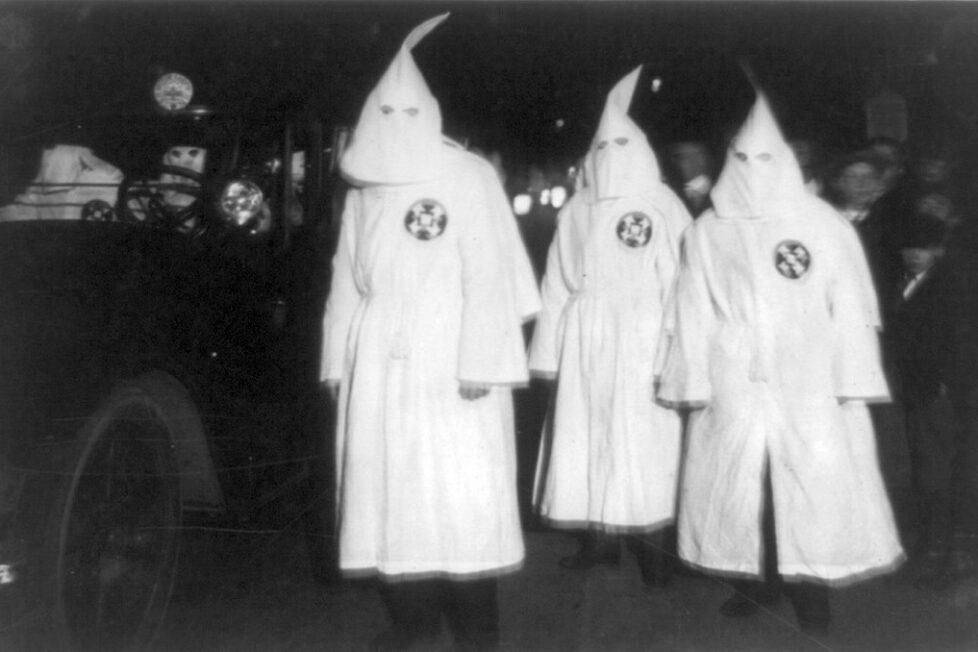

And while Darcy and Sonnefield understandably make the case about punishing Musk for his hate, politicians and others run from accountability to the continued systemic racism toward African Americans. In a cruel irony, after slavery, it was the former slave owners who received reparations, leaving Black Americans to contend with Reconstruction, racist Jim Crow laws, the Ku Klux Klan, redlining, gentrification, the scourge of mass incarceration, and the MAGA movement of today.

The glaring contrast between the uproar over Musk’s potential punishment for hate against the Jewish community and the relative silence on the persistent struggles faced by Black Americans throughout history should serve as a call to action. The African American plead for societal introspection, urging an acknowledgment of uncomfortable truths and a collective commitment to dismantle deeply ingrained structures perpetuating racial disparities. The historical resonance of Wells’ crusade, coupled with the enduring contemporary challenges the Black community faces, underscores the urgency for genuine, systemic change.