Is Black ‘trauma genre’ the new ‘meal ticket’ for Black Hollywood?

Author's note: This is an opinion piece. We welcome you to share your feedback.

Author's note: This is an opinion piece. We welcome you to share your feedback.

The Black community watched in awe as Jordan Peele masterfully combined racial elements to traditional horror in the Academy Award winning film Get Out. While the film did speak to historical events such as slave auctions and the dehumanization of Black people, it was not centered around Black suffering.

Peele has become a pioneer in the world of horror, and for better or worse (emphasis on worse) it seems many other up-and-coming Black creators are riding on his coattails.

Black trauma porn, you might have seen something about it on Twitter or on an angry review about new Black horror movies, but what exactly is it? It is defined as media that exploits traumatic moments for notoriety or attention. It seems for many Black creators, notoriety comes from sensationalism and a complete disregard for Black viewers.

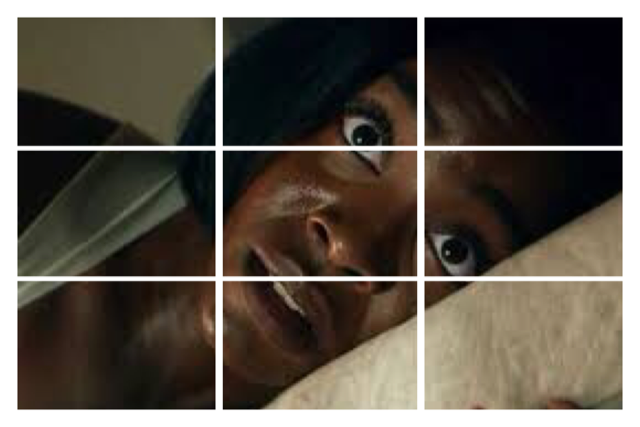

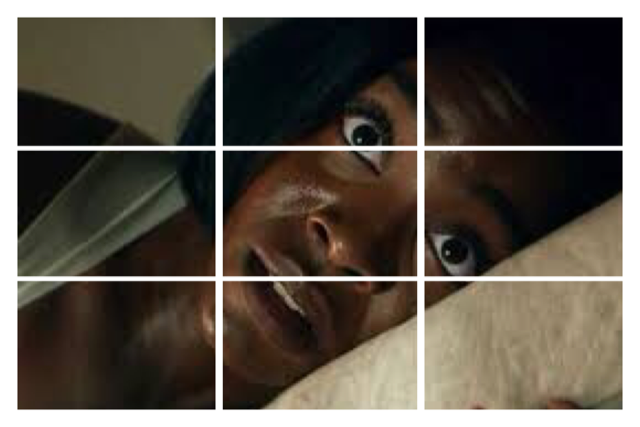

One of the newest Peele knock-offs is the limited Amazon Prime series Them: Covenant, written by Little Marvin and produced by Lena Waithe. The 10-episode series features the Emorys, a Black family in the 1950s moving from Jim Crow South to sunny Compton, California. Henry (Ashley Thomas), an engineer and World War II veteran, Lucky (Deborah Ayorinde) the matron, and their two daughters Ruby (Shahadi Wright Joseph) and Gracie (Melody Hurd) endure hatred and violence from both supernatural beings and white neighbors.

Spoiler Alert:

Episode 5 gives the audience insight into what led the Emorys to leave North Carolina. While Henry and the girls are away, a white woman shows up on the Emory’s property with an interest in the youngest Emory, Chester. As the white woman and two other white men break into the Emory’s house, Lucky hides the infant Chester. Lucky and the baby are found, and while Lucky is brutally raped by the two men, the white woman puts Chester in a sack and swings him back and forth until he dies.

In an explanation for the gory scenes in the series, Little Marvin tells LA Times, “What I’ve come to realize is that I wanted a scene that would rip through the screen, grab the viewer by the jugular and force them to contend with a history of violence against Black bodies in this country. If I did it in a way that you’ve seen before…like an act of police brutality or a slave narrative…that in some way creates a distance or a salve for a viewer. ‘I’ve seen it before.’ But this is so abominable it defies you to see it that way.”

And with this statement the only question I have to ask is “Who is this series really for?”

It can’t possibly be for Black viewers. In what way does police brutality act as a salve for the Black community? Unfortunately, we don’t need a sensationalist scene or series to force us to contend with the history of violence against the Black community. It’s our reality. It’s not just history, it’s happening now.

And ‘Black bodies?’ Come on. Violence is being inflicted on Black PEOPLE. Violence is being inflicted upon the Black psyche, our emotional health, how we interact with one another, along with our physical bodies.

While many people have taken to social media to express their disdain with the series, many others have come out in support. One of the most common arguments made by supporters is that these stories need to be told repeatedly so that we don’t forget.

But how can we forget? Lynching, abuse, brutality are still experienced by the Black community, just in a more modern form. These stories are still happening. More stories are being added to the collection of the horrors and tribulations of the Black community.

Our biggest threat isn’t forgetting the violence inflicted upon us, it’s normalizing that violence.

According to the Encyclopedia of International Media and Communications, desensitization is a psychological process in which the action aspect that arises out of emotion becomes unimportant.

Repeated exposure to media violence over time leads to less sympathy for victims of abuse, and a decrease in emotional response to injury, violence, and death.

What are we subjecting ourselves, and future generations to? Between the death and torture of Black people being recorded and displayed on social media and the news, and the death and torture being displayed in cinema with surface level intentions, Black people are contributing to our own desensitization of Black trauma and death.

I can’t help but think that Black creators in film are creating a new caricature of the ever suffering Negro for financial gain at the expense of the Black community.

Maybe one day we’ll learn that representation isn’t enough. We can’t just depend on Black people in predominantly white spaces because they’re Black. Going forward, we have to be sure that the Black creators we celebrate have the best intentions for the Black community and are not just chasing a meal ticket.